Health is a crown on the heads of the healthy that only the sick can see.

Vomiting and Obstructions in the Upper Gastrointestinal Tract 🔬

Learn how upper digestive tract blockages can lead to emesis (vomiting), including common causes, symptoms, and when to seek medical help.

GASTROINTESTINAL

Dr Hassan Al Warraqi

5/29/20257 min read

🔬Emesis and Upper Digestive Tract Blockages

Understanding Upper GI Obstruction and Vomiting

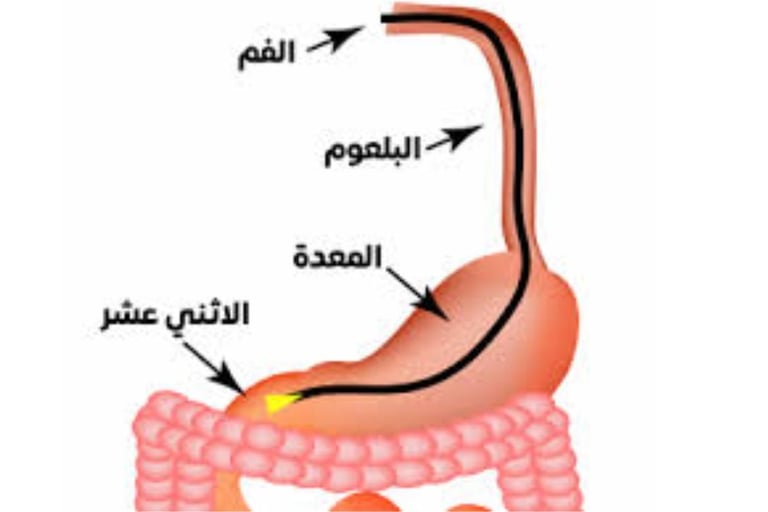

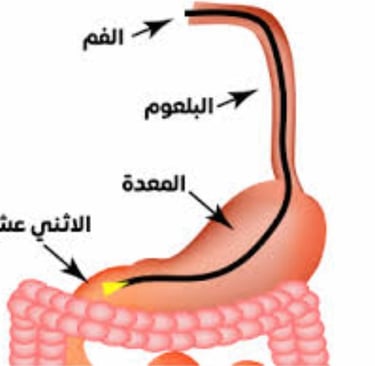

Upper gastrointestinal obstruction represents a serious medical condition where the normal passage of food, liquids, and digestive secretions becomes blocked anywhere from the esophagus to the proximal jejunum. This blockage triggers a cascade of physiological responses, with vomiting being the most prominent and distressing symptom.

The pathophysiology involves mechanical impedance to gastric emptying, leading to progressive gastric distension. As intragastric pressure rises, mechanoreceptors in the gastric wall activate vagal afferent pathways that communicate with the area postrema and nucleus tractus solitarius in the medulla oblongata. This neural activation ultimately triggers the coordinated vomiting reflex through the central pattern generator in the medullary reticular formation.

Detailed Classification of Upper GI Obstruction Causes

Esophageal Obstructions

Structural Abnormalities:

Esophageal strictures from gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) create progressive narrowing through chronic inflammation and fibrosis

Schatzki rings and webs represent focal areas of mucosal or submucosal narrowing

Congenital anomalies like esophageal atresia or tracheoesophageal fistula in pediatric populations

Neoplastic Causes:

Primary esophageal carcinomas, including squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma

Metastatic disease from lung, breast, or other primary sites

Benign tumors such as leiomyomas or gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs)

Functional Disorders:

Achalasia involves failure of lower esophageal sphincter relaxation combined with absent esophageal peristalsis

Diffuse esophageal spasm creates uncoordinated contractions

Jackhammer esophagus characterized by hypercontractile peristalsis

External Compression:

Vascular rings and aberrant vessels compressing the esophagus

Mediastinal masses including lymphadenopathy or thyroid enlargement

Hiatal hernias with significant anatomical distortion

Gastric Outlet Obstruction

Peptic Ulcer Disease Complications:

Duodenal ulcers causing inflammatory edema and scarring at the pyloric channel

Gastric ulcers along the lesser curvature affecting gastric emptying

Chronic scarring from Helicobacter pylori-associated ulceration

Neoplastic Gastric Outlet Obstruction:

Gastric adenocarcinoma, particularly antral tumors

Pancreatic head carcinomas compressing the duodenum

Duodenal adenocarcinomas and periampullary tumors

Lymphomas affecting the gastroduodenal region

Congenital and Developmental:

Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis with muscular hypertrophy

Congenital pyloric atresia or stenosis

Duodenal atresia and annular pancreas in neonates

Inflammatory Conditions:

Crohn's disease affecting the duodenum with stricture formation

Eosinophilic gastroenteropathy causing wall thickening

Caustic ingestion injuries leading to strictures

Duodenal and Proximal Jejunal Obstructions

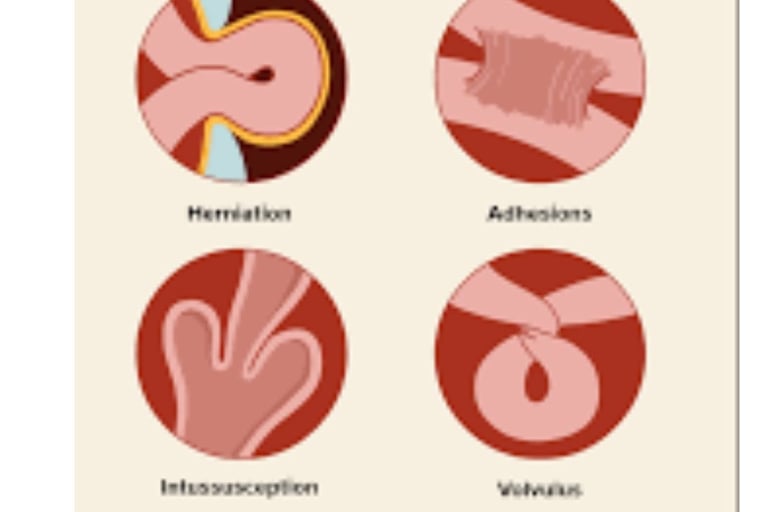

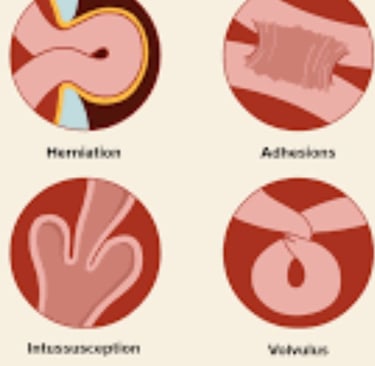

Mechanical Obstructions:

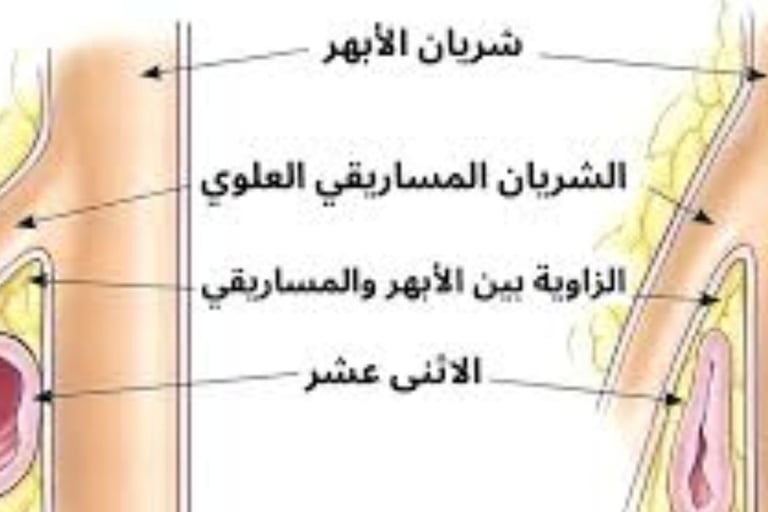

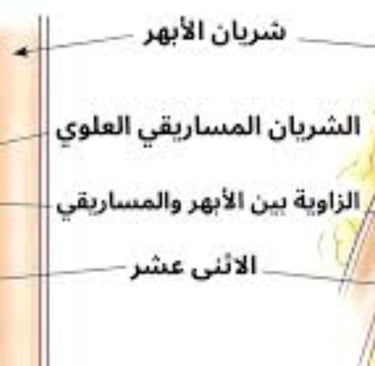

Superior mesenteric artery syndrome compressing the duodenum

Gallstone ileus with impaction at the ileocecal valve

Bezoard formation from undigested material accumulation

Intussusception in pediatric populations

Inflammatory and Infectious:

Duodenal hematomas from trauma or anticoagulation

Parasitic infections like Ascaris lumbricoides causing bolus obstruction

Tuberculosis affecting the duodenum in endemic areas

Postoperative Complications:

Adhesive bands from previous abdominal surgeries

Anastomotic strictures following gastrojejunostomy

Afferent loop syndrome after Billroth II reconstruction

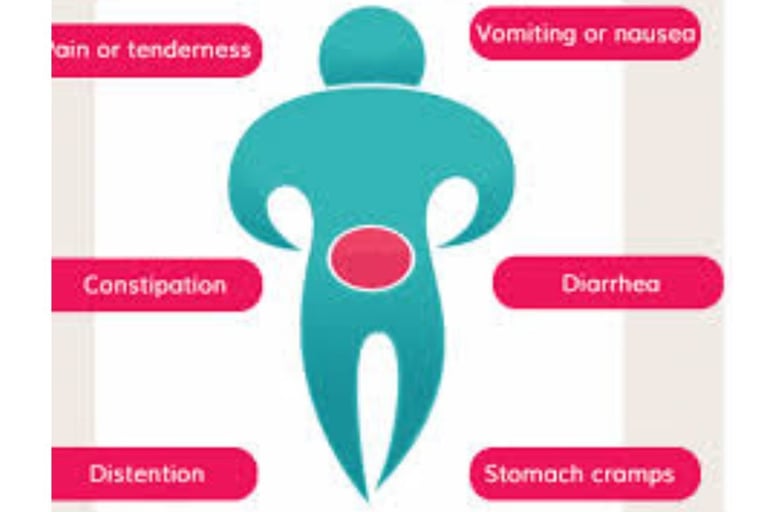

Clinical Manifestations and Symptom Patterns

Early Stage Symptoms

The initial presentation of upper GI obstruction typically involves subtle symptoms that progressively worsen. Patients experience postprandial fullness, early satiety, and intermittent nausea. The vomiting pattern provides crucial diagnostic clues about the location and severity of obstruction.

Esophageal obstructions manifest as regurgitation of undigested food particles, often occurring within minutes of eating. Patients may describe a sensation of food "sticking" in the chest, accompanied by substernal discomfort or pain. Unlike true vomiting, regurgitation lacks the forceful abdominal contractions and prodromal nausea.

Progressive Symptom Development

As obstruction becomes more complete, vomiting becomes more frequent and severe. Gastric outlet obstruction produces characteristic vomiting of partially digested food that may occur several hours after eating. The vomitus often contains recognizable food particles and may have a foul, fermented odor due to bacterial overgrowth in the stagnant gastric contents.

The timing relationship between eating and vomiting helps localize the obstruction level. Immediate regurgitation suggests esophageal pathology, while delayed vomiting (4-6 hours post-meal) indicates gastric outlet or duodenal obstruction.

Advanced Complications

Chronic upper GI obstruction leads to significant nutritional consequences. Progressive weight loss occurs due to reduced oral intake and malabsorption. Dehydration develops from persistent vomiting and reduced fluid intake. Electrolyte imbalances, particularly hypokalemic hypochloremic metabolic alkalosis, result from loss of gastric acid and potassium.

Diagnostic Approach and Imaging Studies

Clinical Evaluation

The diagnostic workup begins with a comprehensive history focusing on symptom onset, progression, and associated factors. Physical examination may reveal gastric distension, visible peristalsis in thin patients, or a succession splash when shaking the patient's abdomen.

Laboratory Studies

Initial laboratory evaluation includes complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and liver function tests. Electrolyte abnormalities commonly include hyponatremia, hypokalemia, and hypochloremia. Elevated blood urea nitrogen may indicate dehydration, while low albumin suggests malnutrition.

Imaging Modalities

Upper Endoscopy: Provides direct visualization of mucosal abnormalities, allows tissue sampling, and enables therapeutic interventions like dilation or stent placement.

Upper GI Series: Barium studies outline anatomical abnormalities and demonstrate the level of obstruction through delayed gastric emptying.

CT Imaging: Cross-sectional imaging identifies masses, external compression, and complications like perforation or abscess formation.

Nuclear Medicine Gastric Emptying Studies: Quantify gastric emptying rates and help distinguish mechanical from functional obstruction.

Treatment Strategies and Management Approaches

Conservative Management

Initial treatment focuses on stabilizing the patient's condition through fluid resuscitation and electrolyte correction. Nasogastric decompression relieves gastric distension and reduces vomiting episodes. Proton pump inhibitors reduce gastric acid secretion and may help with associated peptic ulcer disease.

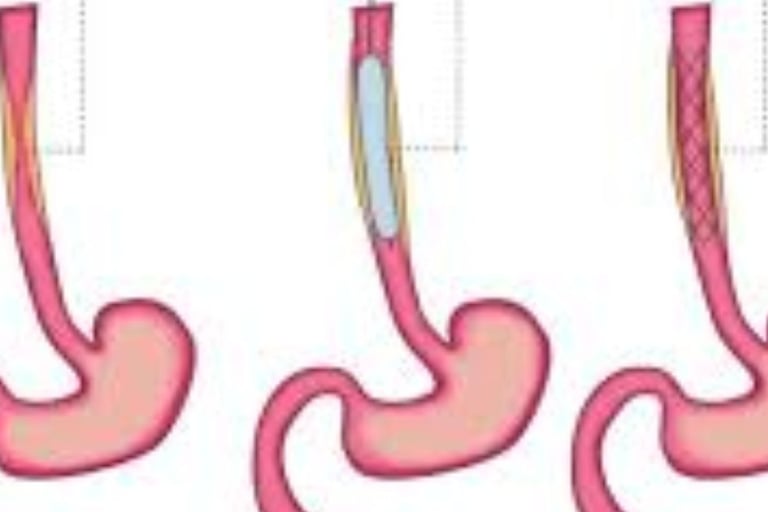

Endoscopic Interventions

Therapeutic endoscopy offers minimally invasive treatment options for many obstructive conditions. Pneumatic dilation effectively treats achalasia and benign strictures. Stent placement provides palliative relief for malignant obstructions. Endoscopic mucosal resection or submucosal dissection may remove small neoplastic lesions.

Surgical Management

Definitive surgical treatment depends on the underlying pathology and patient factors. Pyloroplasty or gastrojejunostomy bypass gastric outlet obstruction. Esophagectomy may be necessary for malignant esophageal obstructions. Laparoscopic approaches minimize surgical morbidity when technically feasible.

Complications and Long-term Outcomes

Immediate Complications

Aspiration pneumonia represents a serious risk from recurrent vomiting, particularly in elderly patients or those with altered mental status. Mallory-Weiss tears can occur from forceful vomiting, potentially leading to upper GI bleeding. Boerhaave syndrome, though rare, represents full-thickness esophageal rupture requiring emergency surgical intervention.

Chronic Consequences

Prolonged obstruction leads to gastric atony and delayed gastric emptying even after successful treatment. Nutritional deficiencies develop from malabsorption and reduced intake. Chronic dehydration may result in acute kidney injury, particularly in elderly patients with underlying renal disease.

Prevention and Risk Reduction

Primary Prevention

Early treatment of peptic ulcer disease and GERD reduces the risk of developing obstructive complications. Helicobacter pylori eradication prevents ulcer recurrence and associated scarring. Regular cancer screening in high-risk populations enables early detection of malignant causes.

Secondary Prevention

Patients with known risk factors require regular monitoring and surveillance. Endoscopic surveillance identifies early stricture formation or malignant transformation. Nutritional counseling helps maintain adequate intake despite anatomical limitations.

SEO-Optimized Content Summary

Upper gastrointestinal obstruction causing vomiting represents a complex medical condition requiring prompt recognition and appropriate treatment. Understanding the various causes, from peptic ulcer complications to malignant obstructions, enables healthcare providers to develop effective treatment strategies. Early diagnosis through comprehensive evaluation and appropriate imaging studies improves patient outcomes and reduces complications.

The management approach must be individualized based on the underlying pathology, patient comorbidities, and severity of obstruction. While conservative measures may suffice for mild cases, severe obstructions often require endoscopic or surgical intervention. Long-term follow-up ensures optimal outcomes and prevents recurrence.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) about Emesis and Upper Digestive Tract Blockages

Q: What are the most common causes of upper GI obstruction leading to vomiting?

A: The most common causes include peptic ulcer disease with pyloric stenosis, gastric outlet obstruction from tumors, esophageal strictures from GERD, and duodenal obstructions. In infants, hypertrophic pyloric stenosis is the leading cause.

Q: How can I differentiate between mechanical obstruction and functional causes of vomiting?

A: Mechanical obstruction typically presents with consistent symptoms that worsen over time, visible gastric distension, and characteristic imaging findings. Functional causes often have intermittent symptoms, normal anatomy on imaging, and may respond to prokinetic medications.

Q: What are the warning signs that indicate urgent medical attention for GI obstruction?

A: Warning signs include severe dehydration, persistent inability to keep fluids down, severe abdominal pain, signs of perforation (fever, rigid abdomen), significant weight loss, or symptoms of aspiration pneumonia.

Q: How long does recovery take after treatment for upper GI obstruction?

A: Recovery time varies significantly based on the underlying cause and treatment method. Endoscopic interventions may provide immediate relief, while surgical procedures require weeks to months for full recovery. Chronic conditions may require ongoing management.

Q: Can upper GI obstruction recur after successful treatment?

A: Yes, recurrence is possible depending on the underlying cause. Benign strictures may re-stenose, requiring repeated interventions. Malignant causes have high recurrence rates. Regular follow-up is essential for early detection and management of recurrent obstruction.

Q: What dietary modifications are recommended for patients with upper GI obstruction?

A: Dietary recommendations include eating smaller, more frequent meals, thoroughly chewing food, avoiding hard-to-digest items, staying upright after eating, and maintaining adequate hydration. Liquid or pureed diets may be necessary for severe cases.

Q: Are there any medications that can help with symptoms of upper GI obstruction?

A: Prokinetic agents like metoclopramide may help with mild functional components, while proton pump inhibitors reduce acid secretion. Antiemetics can provide symptomatic relief, but definitive treatment usually requires addressing the underlying obstruction.

Q: What is the prognosis for patients with malignant upper GI obstruction?

A: Prognosis depends on the primary tumor type, stage, and patient factors. While curative resection may be possible for early-stage disease, advanced malignant obstruction often requires palliative interventions focused on symptom relief and quality of life improvement.

Keywords

Treatment of gastric obstruction - Vomiting after eating - Symptoms of intestinal obstruction - Difference between mechanical and functional obstruction - When is vomiting serious?

✍️ About the Author

Hassan Al-Warraqi is the founder of H-K-E-M.com and a medical writer focused on digestive health, metabolic disorders, and natural interventions. With a deep interest in gastrointestinal physiology, Hassan breaks down complex topics like upper GI obstructions, vomiting mechanisms, and the systemic impacts of delayed gastric emptying.

His mission is to empower readers with evidence-based insights to recognize warning signs early and pursue informed, holistic care.

📱 Short Social Media Version

🖋️ By Hassan Al-Warraqi

Founder @h_k_e_m_com | Exploring vomiting, gut blockages & upper GI health 🔬🩺🤢